Bank of Canada keeps interest rate FLAT!

25 Apr 2019

Canadian interest rates are almost certainly on hold until at least sometime next year.

The Bank of Canada published a revised outlook on Wednesday that shows the economy stalled over the last six months, extinguishing the sparks that had caused policy makers to starting worrying about inflation.

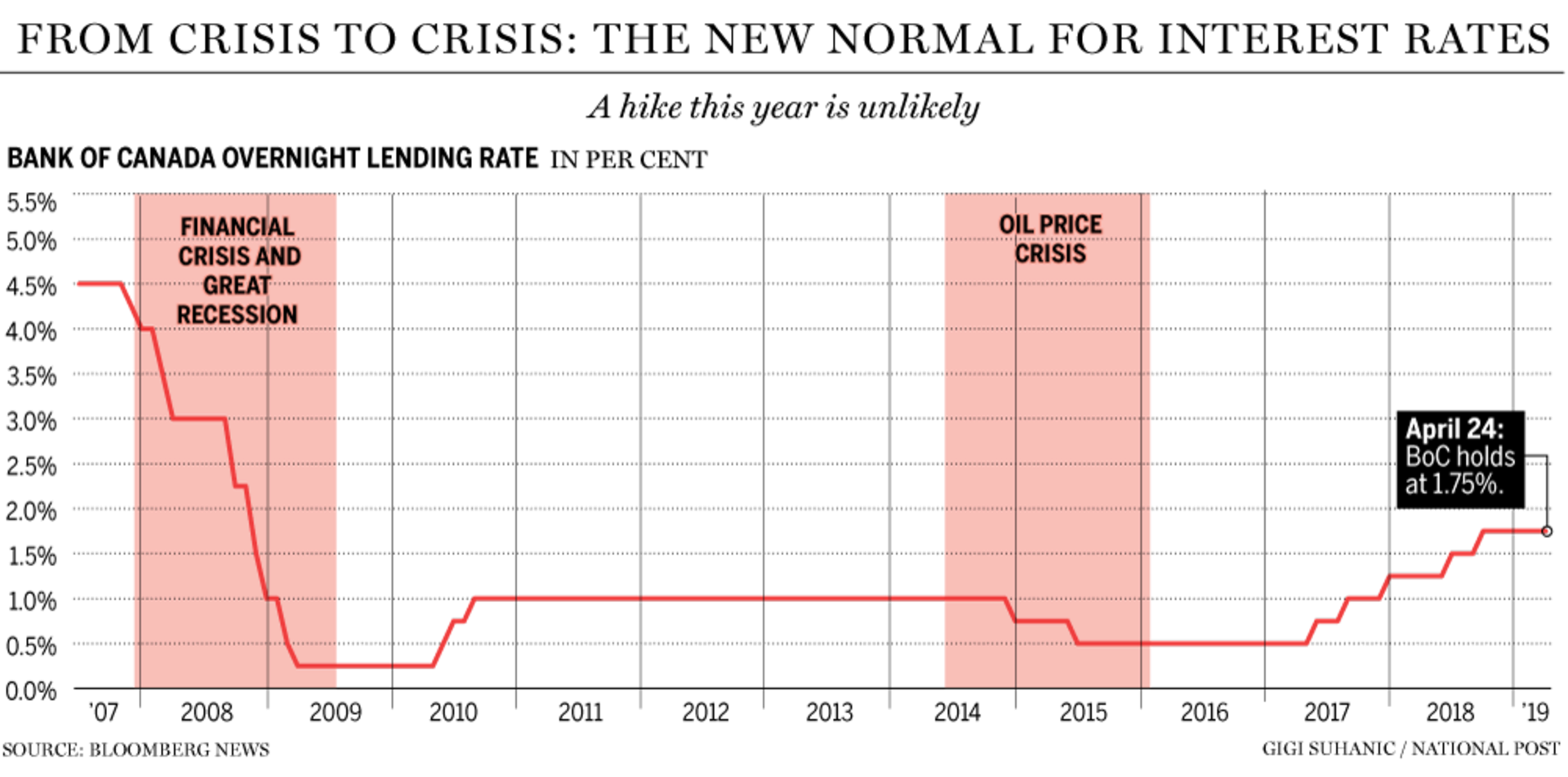

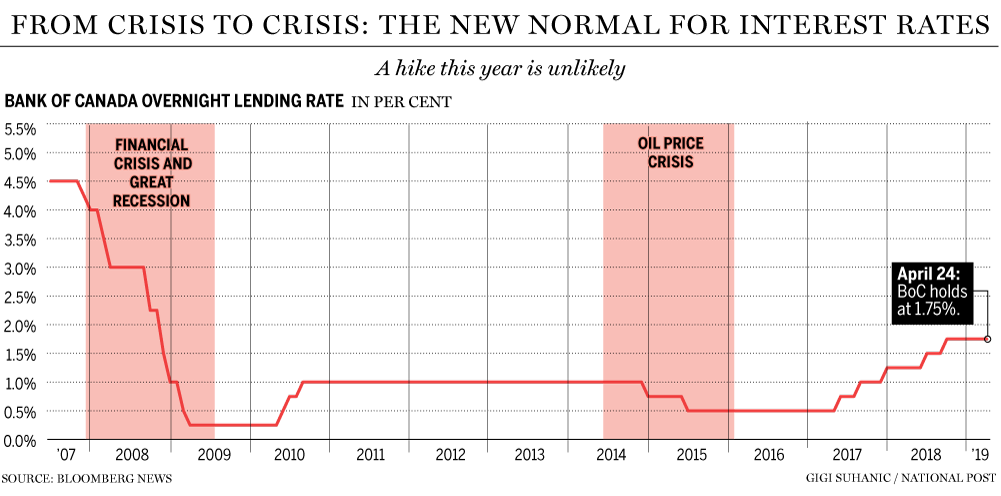

Governor Stephen Poloz and his deputies left the benchmark rate unchanged at 1.75 per cent, as expected. They also erased from their policy discussionany suggestion that interest rates could rise in the foreseeable future, a pivot that suggests the pause that began in December is now a hiatus.

Poloz called it a “detour,” as the Bank of Canada’s revised forecast predicts the economy will rebound to growth of around two per cent in 2020. Still, he conceded at a press conference that the economy currently is so fragile that a negative shock would force policy makers to consider cutting interest rates.

“If everything turns out perfectly, there’s no rush to suddenly get back in the saddle” and resume raising interest rates, Poloz told reporters. “It’s more a question of letting the data speak,” he added. “Right now, we need some positive data to confirm that this outlook is the appropriate one.”

The value of the Canadian dollar dropped by nearly a penny to roughly 74 U.S. cents, as traders repriced financial assets to match a prolonged period of low borrowing costs. The yield on overnight index swaps now implies that investors are hedging against the possibility of lower interest rates through next year, even though Poloz said the central bank’s outlook implies that odds still favour increases over cuts.

“Although we don’t see an argument for rate hikes at this stage, we also don’t think an outlook that calls for continued low unemployment and near two-per-cent inflation warrants a reversal of the BoC’s recent moves,” said Josh Nye, an economist at Royal Bank of Canada, who correctly predicted that the central bank would back away from raising the policy rate this year. “Our forecast assumes the overnight rate will be held at 1.75 per cent through next year, so expect more steady rate decisions in the months ahead.”

Canada’s economy was cruising at the start of the last year when a plunge in oil prices, higher interest rates, and U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade wars converged to create a torrent of headwinds.

Gross domestic product was growing at an annual rate of two per cent in the third quarter, then decelerated to rates of 0.4 per cent in the fourth quarter and 0.3 per cent in the first three months of this year, according to the central bank’s new quarterly Monetary Policy Report (MPR).

Those numbers will keep alive talk that Canada is on the verge of a recession. The central bank — and many others — failed to detect the severity of the slowdown. In October, policy makers predicted GDP would grow at an annual rate of 2.3 per cent in the fourth quarter, and then in January they revised that estimate to 1.3 per cent. They also were overly optimistic about growth in the first quarter, predicting an annual rate of 0.8 per cent in the January MPR.

Policy makers said in the MPR that they correctly adjusted for the drag from lower oil prices. Their mistake was assuming that non-energy exports would gather momentum and that executives would increase investment in order to keep up with demand. Instead, both have struggled, robbing the economy of an offset to a decline in spending on real estate and weaker household consumption.

The central bank now predicts GDP will expand only 1.2 per cent in 2019, compared with a January estimate of 1.7 per cent. It would be the weakest growth since 2015-16 period, when the country barely avoid a recession.

“No one likes to make forecast errors of any size, but we know it’s part of the business,” Poloz said. “The main thing we were trying to do is capture something that it quite ephemeral, business sentiment, which translates into investment decisions,” he added. “Maybe that sounds to you like an excuse, but I think it’s the reality, in that you are trying to forecast something that really isn’t forecastable.”

The prediction business is hard. Still, the big miss last year could undermine confidence in the Bank of Canada’s prediction that the soft patch is essentially over. The Bank of Canada predicts a rebound in the second half, sparked by an annual growth rate of 1.3 per cent in the current quarter. Higher levels of immigration should help stabilize the housing market, “strong” increases in labour income will support consumption, and a rebound in global economy will force maxed-out non-energy exporters to invest in order to keep up with demand, the central bank said in its policy statement.

But an expected recovery isn’t an offset for damage done. At the start of the year, the central bank thought the economy was generating output at a level that puts upward pressure on prices. It now says there is an “output gap” of between 1.25 per cent and 0.25 per cent.

Policy makers also revised their estimate of the non-inflationary growth rate to 1.8 per cent, considerably faster than their outlook for 2019. Containing inflation no longer is an issue, so the central bank can now focus on generating some.

“Governing Council is of course preoccupied with the recent slowdown in the economy,” Poloz said in his opening statement to reporters, an important document the central bank uses to add context to policy decisions. “If it were to persist, then we would foresee inflation trending below target in the future.”